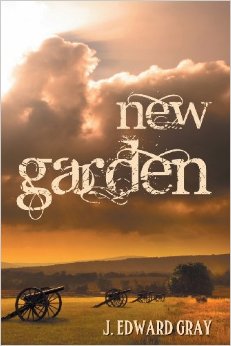

When I traveled California Route 395 to Yosemite from Reno 14 years ago for a family vacation, I had no idea that Mono Lake and the Sierra Nevada would serve as the setting for a major segment of a future novel. My first novel, New Garden (2013), opens in the High Sierra. My second novel, a stand-alone sequel to New Garden that should be available by March 2015, includes one major section where the action takes place in the High Sierra and the Mono Basin.

But when the California State Park Ranger told my tour group about kutsavi (see October 1, 2013 article on this blog), I knew I would work it into a future story. And I did, telling how the food source allowed my protagonist, Jack Grier, to survive a winter at Mono Pass.

As part of my research, I came across Up and Down California in 1860-1864; the Journal of William H. Brewer. Mr. Brewer served on Josiah Whitney’s geological survey team during the stated time period. In his journal, Brewer describes his 1863 experience at Mono Lake:

Lake Mono

July 9 we came on about ten miles north over the plain and camped at the northwest corner of Lake Mono. This is the most remarkable lake I have ever seen. It lies in a basin at the height of 6,800 feet above the sea. Like the Dead Sea, it is without an outlet. * * * * The waters are clear and very heavy – they have a nauseous taste. When still, it looks like oil, it is so thick, and it is not easily disturbed. Although nearly twenty miles long it is often so smooth that the opposite mountains are mirrored in it as in glass. The water feels slippery to the touch and will wash grease from the hands, even when cold, more readily than common hot water and soap. I washed some woolens in it and it was easier and quicker than in any “suds” I ever saw. It washed our silk handkerchiefs, giving them a luster as if new. It spots cloths of some colors most effectually.

At the time, the territory east of the Sierra Nevada was chock-full of boom-and-bust mining towns. Brewer describes the region, including the bustling town (population of approximately 5,000) of Aurora:

Immense sums of money have been spent here in this region, an immense number of claims have been taken up, nearly twenty quartz mills have been erected . . .; but whether the mines will ever pay is to me a question. * * * One or two mines may pay, the majority never will.

Where Aurora is, is as yet known. We think it in California, but there is a dispute whether it be not over the line and in Nevada Territory. Most of the inhabitants wish it there, so that Uncle Sam will pay their bills of government, but like true American citizens, who will not be deprived of their rights, they vote in both places, in California and in Nevada, and their votes have thus far been accepted in both.

Aurora was ultimately determined to be three miles inside the Nevada line.

Mono Lake was a valuable resource to Aurora’s residents, because some men made a living by gathering duck eggs from Mono Lake’s islands and selling them in Aurora for $1.00 to $1.50 per dozen ($30-$45 in 2014 U.S. dollars).

Whenever I travel south on California 395, I can’t help but think of the old mining towns and the steep prices the miners paid for life’s necessities. Mostly, however, I enjoy the jaw-dropping views from Vista Point – ancient Mono Lake dead ahead; the White Mountains to the east; the Sierra Nevada to the west; the Mono Craters just beyond Mono Lake. It’s another incredible experience before driving west up Tioga Road into the stunning High Sierra.

For more information about Mono Lake, check out the following websites: