This is the ninth in a series of articles in which I share my methodology for crafting a story, which I hope is both interesting and informative. In my last post, I wrote about the Carmel Mission. This week, I turn to the Mariposa Indian War, one of all-too-many tragic engagements between white Americans and the native tribes in the American West.

Among the sources I cite at the conclusion of New Garden are Barrett and Gifford’s Indian Life of the Yosemite Region, Miwok Material Culture (republished by Yosemite National Park, Yosemite Association); Sarah Lee Johnson’s Roaring Camp – The Social World of the California Gold Rush; H.W. Brands’ The Age of Gold; and Lafayette Bunnell’s Discovery of the Yosemite and the Indian War of 1851.

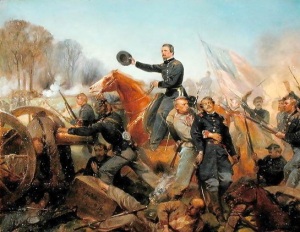

I employed these sources when I adapted Bunnell’s account to the story. Jack Grier, New Garden’s main character, heads up a Gold Rush trading company, Sierra Dry Goods. Jack becomes a captain in the state militia organized to punish the local tribes after two of his men are killed at one of his trading posts. In actuality, the tribes attacked the trading post of another supplier, Jim Savage. I have modeled Jack’s role after that of Captain John Boling, who served under Savage. I deviate from Bunnell’s account where necessary to bring interest to the story.

First, I give the reader an understanding of the native tribes’ presence in the Sierra Nevada long before the California Gold Rush, in a chapter captioned “Two Hundred Generations” (pp. 115-116).

Twenty-seven thousand years ago, their ancestors crossed the Bering Strait land bridge to Alaska. Twelve thousand years ago, their ancestors migrated to California and lived primarily along the coast and southern California. Five thousand years ago, their ancestors migrated inland.

By 1849, more than two hundred generations of Miwoks and Yokuts had lived in the Sierra Nevada foothills. The men had hunted deer, bear, and smaller game. They had fished the Sierra’s rivers. The women had experimented with native plants and made use of their properties for both food and medicine.

***

More than two hundred generations of Miwoks and Yokuts had lived in harmony with the land. They had no need to plant crops. They lived in the world’s most abundant garden, which only required harvesting.

By 1848, smallpox and other diseases brought by the Spanish had cut California’s native population in half, from 300,000 to 150,000. Two years after the discovery of gold, the state’s native population fell another 50,000. By 1851, the white miners’ destruction of forests and game threatened the survival of the Sierra Nevada tribes. After an Indian raid on one of Savage’s trading posts, the whites used the attack as an excuse for driving the tribes out of the mountains to a reservation in Fresno.

The war was more of a “herding” or gathering of the tribes, with limited armed engagements. The tribes included the Ahwahnechee, whose members consisted of a mix of the Miwoks of the Western Sierra and the Monos of the Eastern Sierra. As the “war” neared its end, two soldiers murdered the son of Ahwahnechee Chief Tenaya. Bunnell recounts Chief Tenaya’s reaction. I have replicated Bunnell’s account on pages 124-125 of New Garden, except to expand on it (in italicized language) to provide for a dramatic impact on Jack’s life (expanded later in the story):

Kill me, Captain. Yes, kill me, as you killed my son; as you would kill my people if they were to come to you! You would kill my race if you had the power. *** [W]hen I am dead I will call to my people to come to you, I will call louder than you have heard me call; that they shall hear me in their sleep, and come to avenge the death of their chief and his son. Yes, sir, American, my spirit will make trouble for you and your people, as you have caused trouble to me and my people. May you grieve the death of your son as I shall grieve the death of my mine.

The Mariposa Battalion ultimately succeeds in removing the local tribes to a reservation, but Tenaya’s curse haunts Jack later in the story.

Please consider a longer read. New Garden is available on line from Amazon, Apple, and Barnes & Noble. Each website includes a “look-in” feature with the first few chapters of the novel. In Greensboro, NC, the novel is available at Scuppernong Books and the Greensboro Historical Museum Bookshop.

The sequel, Trouble at Mono Pass, is available on line and at the referenced Greensboro locations. In California, it is available at the Mono Lake Tufa State Reserve (Lee Vining) gift shop, the Mono Lake Committee Bookstore (Lee Vining), and the Donner Memorial State Park Bookstore (Truckee, California).