This month marks the 150th anniversary of Union General U.S. Grant’s campaign to destroy Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

As Virginia’s many rivers go, the Rapidan receives scant notice. Its headwaters begin 4,000 feet above sea level near the Big Meadows in the Blue Ridge. From there, the river descends east, gradually widening until it flows into the Rappahannock River northwest of Charlottesville and Fredericksburg. During the winter of 1863-1864, every American identified the river as the boundary line between General Meade’s Army of the Potomac and Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia.

On Wednesday, May 4, 1864, Grant sent Meade’s 120,000 soldiers across the Rapidan on pontoon bridges constructed by the army’s engineers at two points: Ely’s Ford and Germanna Ford. Grant was determined to destroy Lee’s 60,000-man army and capture Richmond in the process.

Throughout the month of May, Grant and Lee danced their deadly Tarantella, suffering losses in proportion to their numbers. In the Battles of the Wilderness and Spotsylvania Court House, the Union army suffered casualties – killed, wounded, or captured – of 36,000 men while the Confederate casualties totaled 24,000. To put the losses in perspective, one has to remember that the United States population today is ten times that of 1864 (taking into account populations both north and south).

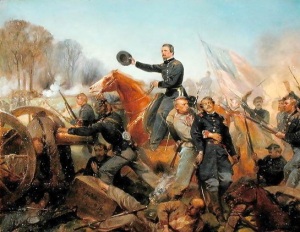

Battle of the Wilderness, Attack at Spotsylvania Courthouse, Virginia, 1865; Painting by Alonzo Chappel (Source: 1stArtGallery.com)

Despite the heavy losses, Grant continued forward, unlike the Union commanders who preceded him. He made “turn the left flank” the order of the day, and by Thursday, June 2, Union troops had fought their way within ten air miles of Richmond. Both commanders replenished their losses. Grant received 40,000 fresh troops in the second half of May, most from the “heavy artillery” units in and around Washington, who previously had seen action only on Washington’s parade grounds. Lee had to move Confederate troops south of Richmond and in North Carolina to bring his troop strength back to his original 60,000. By doing so, Lee risked a rout from the rear.

June would open with a shocking loss for the Union troops. I will address that in another article.

Most of this brief account is taken from my Civil War era novel, New Garden (pages 275-276), available on line from Amazon, Apple, Barnes & Noble, and Dog Ear Publishing. The novel is also available in Greensboro, NC, at the Greensboro Historical Museum and Scuppernong Books.

For historical sources about Grant’s campaign, I recommend the following:

- Catton, Bruce. Never Call Retreat. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1965 (republished by Fall River Press, New York, NY, in 2001).

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War, A Narrative, Red River to Appomattox. New York, New York: Random House, 1974.