In my most recent article, I described the battle of Cold Harbor as Grant at his worst and at his best. I said enough about Grant at his worst. Now about Grant at his best. He could have sat at Cold Harbor, numbed by a horrible loss, just hoping to keep Lee and his Army of Northern Virginia at bay while Sherman drove through Georgia. But he obviously did not. He remained resilient.

In later years, he acknowledged his failure at Cold Harbor. But he aimed to destroy Lee’s army. To do so, he had to stretch Lee’s troops to the breaking point. If Grant could lay siege to Richmond and Petersburg, Lee knew surrender was only a matter of time. Grant did so in a way that in retrospect may be perceived as reckless, but was bold in design and brilliant in execution.

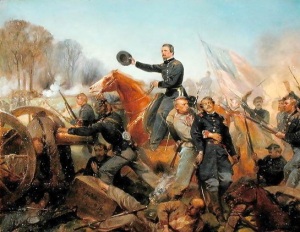

On Tuesday, June 7, General Phil Sheridan led two Union cavalry divisions northwest toward Charlottesville. Lee had no choice but to order General Wade Hampton to respond in kind, taking his cavalry to intercept Sheridan. The cavalry served as the commander’s eyes, scouting the enemy’s movements. Without Hampton in the vicinity of Cold Harbor, Lee could no longer keep an eye on Grant. Of course, that was part of Grant’s plan, along with an assault by General Benjamin Butler on Beauregard’s forces at Petersburg.

Ten miles downriver from Cold Harbor, Grant’s engineers laid a half-mile pontoon bridge across the James River. Had Lee learned about the crossing in time, he could have destroyed Grant’s army. Sheridan’s diversion and the

Union army’s deliberate withdrawal from Cold Harbor allowed Grant to “steal a march” on Lee. By Monday, June 13, the Yankees were across the James and Grant had set up headquarters at City Point (modern day Hopewell). Lee could only hope to prevent Grant from overrunning Richmond. Lee did that much, in part because of Union generals’ blunders, but he could not prevent the Union siege that would drive the Confederate army and local civilians to starvation.

The South’s hopes now lay in holding out until Tuesday, November 8, the date of the national election. If the South could avoid a major loss before that date, Southern leaders were certain Lincoln could not be reelected and that they could negotiate a peace with Lincoln’s successor. That was a big “if.” Sherman drove through Georgia and the Carolinas and Sheridan laid waste to the Shenandoah Valley. By Election Day the only question was Lincoln’s margin of victory.

Historical Sources:

- Catton, Bruce. Never Call Retreat. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Co., 1965 (republished by Fall River Press, New York, NY, in 2001).

- Foote, Shelby. The Civil War, A Narrative, Red River to Appomattox. New York, New York: Random House, 1974.

- Grant, Ulysses S. The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant. New York, New York, 1886 (republished by Konecky & Konecky, Old Saybrook, Connecticut).