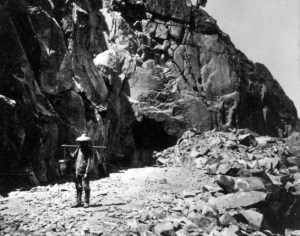

Chinese transcontinental railroad workers. Photo taken in 1869. (Source: Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center)

As I mentioned in my last article, this past May, I visited the California Railroad Museum in Sacramento. While there, our excellent tour guide credited Building Superintendent Charley Crocker (who, along with Edwin Crocker, Collis Huntington, Leland Stanford, and Mark Hopkins, ran the Central Pacific) with the two most important executive decisions that made railroad construction possible in the Sierra Nevada: first, hiring thousands of Chinese to perform the labor that white laborers refused to do; second, building over thirty miles of “snow sheds,” which allowed the laborers to work and the trains to run in all but the very worst snow storms.

Last week, I discussed the snow sheds. This week, I will turn my attention to the thousands of Chinese who made such a significant contribution to the construction of the railroad. Most people even vaguely familiar with the building of the transcontinental railroad know that the Chinese made up a significant portion of the workforce. Few people understand why.

The answer has three components: bias against the Chinese; the shortage of white men willing to do the work; and the Chinese work ethic and history of similar construction.

The Chinese arrived in waves shortly after the beginning of the Gold Rush. They spoke a different language, practiced a different religion, dressed differently, and maintained a different diet. More importantly, they enjoyed success finding gold in California’s foothills. White miners often drove them off their claims – the same fate suffered by other foreign miners. Local jurisdictions restricted them from filing mining claims. White miners successfully lobbied for state laws that penalized the Chinese: the Foreign Miners’ License Tax; the Act to Provide for the Protection of Foreigners and to Define Their Liabilities and Privileges; the Act to Discourage the Immigration to This State of Persons Who Cannot Become Citizens Thereof (and a host of others cited in Professor David Bain’s Empire Express, p. 206).

The proximity of Nevada’s Comstock Lode on the eastern side of the Sierra Nevada worked against the Central Pacific’s retention of white laborers, who often worked only long enough to earn money to pay the fare for the Dutch Flat Wagon Road to the east side of the Sierra. The prospect of striking it rich outweighed the certain monthly $30 plus board for back-breaking work. To the Chinese, the lower wage of $26 per month, with which they had to provide their own meals, looked brighter than the certain discrimination and harassment they could expect if they tried to compete with white miners in the silver mines.

Charley Crocker, whose line superintendent, one-eyed James Strobridge, resisted hiring the Chinese to do stonework, famously said, “Didn’t they build the Chinese Wall?” Strobridge, initially one of the Chinese workers’ greatest skeptics, soon became one of their greatest boosters. The Chinese showed up on time and did not lay out the first day of the week (like some white workers who drank their wages on their day off). Before beginning work, the Chinese boiled their tea to take with them to work, thus assuring themselves of a sanitary source of water.

PBS.org Video: Transcontinental Railroad Recruits Chinese Laborers: www.pbslearningmedia.org/resource/akh10.socst.ush.now.trchinese/transcontinental-railroad-recruits-chinese-laborers/

And, as Charley Crocker said, they had built the Great Wall of China. The building methods differed little in the Sierra, where initially gunpowder was the predominant means of blasting through the rock. (The Central Pacific did learn to use the less stable nitro glycerin, which required substantially less drilling than did the gunpowder. John Gillis, American Society of Civil Engineers, “Tunnels of the Pacific Railroad,” 1870.) The Chinese were doing the kind of work they had done for centuries.

Thus, limited economic opportunities (due to bias), a livelihood for which few white men wished to compete, and experience in the construction methods they had to employ, all conspired to make the Chinese available and capable to make their substantial contribution to the wonder of their age, the construction of the railroad through a mountain range many did not think possible to cross.

Rather than honoring the Chinese for their work, California and the United States would continue to discriminate against them, most significantly with the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, which banned all immigration of Chinese laborers.

I wish to reiterate my thanks to the Railroad Museum’s curator, Kyle Wyatt, and librarian, Cara Randall, who so generously provided their time and a wealth of information about the Central Pacific.

Sources:

- Bain, Empire Express, Penguin Group: New York, NY (1999)

- Brands, The Age of Gold, Anchor Books: New York, NY (2003)

- Gillis, American Society of Civil Engineers, “Tunnels of the Pacific Railroad (Jan. 5, 1870)

- Lavender, The Great Persuader, Doubleday: Garden City, NY, (1970)