This is the twelfth in a series of articles in which I share my methodology for crafting a story, which I hope is both interesting and informative. Last week, I wrote about the “Associates,” the principals in the Central Pacific Railroad, the company that built the western leg of America’s first transcontinental railroad. This week, I return to the Civil War, specifically the battle of Cold Harbor.

In an earlier article on this site (May 23, 2014), I spoke about Cold Harbor as a battle which witnessed General Ulysses S. Grant at his worst and at his best. At his worst, because he failed to insure adequate surveillance of his enemy. Lee exacted a bloody, unnecessarily costly price, a fact that Grant acknowledged in his memoirs. It’s difficult to fathom today. On the morning of June 3, 1864, Grant ordered an attack of 60,000 Union soldiers across open ground. Along a seven-mile line, Lee’s soldiers stood safely behind log and earth barriers. The Confederates stacked logs with openings at eye-level, where a soldier could stand and fire his rifle with little danger of being struck by return fire. Artillery units were primed to bombard the enemy. Most of the slaughter was over in eight minutes. Seventeen hundred men lay in windrows. Another nine thousand lay wounded on the field, expecting their commander to request a truce so they could be retrieved from the field.

In New Garden, I lend the battle a personal touch, illustrated by the plight of two brothers at dawn of the fateful day:

Perry McDougal’s thoughts drifted to Hemlock Lake. If he survived the war, he would return there and never leave. He would marry Gloria McBride and have at least ten children. He would gladly leave the war behind him and never speak of its horrors.

It was the only cool part of the day, but Perry was all perspiration. He knew the Federals’ failure to attack the previous day had given Lee too much time. Perry knew it. His brother Tom knew it. All sixty thousand men about to make the frontal assault knew it.

Perry nervously opened his cartridge box, fingering its contents. The paper encasing the ball and powder grew damp with perspiration.

Somehow Perry calmed down as his hands dried.

“Tom,” he whispered.

“Yeah, Perry,” Tom whispered back.

“If you make it, tell Pa I didn’t shirk. I didn’t waver.”

“Shut up, Perry. You’ll make it. Don’t bring us bad luck.”

And then came the horror of the rebel barrage:

The sun then appeared to flash above the horizon, but, no, that wasn’t east. Twenty-five thousand rebel muskets fired, along with over a hundred cannon.

Tom glanced left. Perry had pushed left, as if doing so might save his brother.

The glimpse was horrible. A head, a limb, then the entire mass of his brother disintegrated before him, just as the shock of the rebel explosion threw him to the ground.

Tom awoke, unable to hear anything. He crawled to his right, safe, he thought, in a swale. Minnie balls whistled around him or thudded in his comrades’ bodies, now lying in rows like fallen dominoes.

It wasn’t much, but Tom recognized it instantly. Somehow the blade of a pen knife had survived the volley. Tom could make out the engraving, “Perry A. McDougal” with “1863” beneath the name. Tom had bought the knife in Baltimore for Perry’s birthday last November. The brothers had been safe at the time, pulling artillery duty outside the city. Tom grabbed the blade, then fell back into the swale. He had seen nothing resembling his brother. Tom lay still through the day’s scorching heat, soaked in sweat, with black flies and mosquitoes waiting for him to die. At nightfall he crawled back into the safety of the Union camp.

New Garden, pp. 277-278.

“Unconditional Surrender” Grant had never suffered a defeat on the battlefield. Rather than admit one now, Grant attempted to negotiate a truce, as if the battle had been a draw. Lee would have none of it. Grant persisted, asking that Lee demonstrate humanity toward the “suffering from both sides.” Finally, on Tuesday, June 7, Grant acknowledged defeat and Union soldiers recovered their brethren under a flag of truce. Only two Union soldiers remained alive on the field. Any other survivors had crawled back into Union lines under cover of darkness. For many, the delay had sealed their doom or cost them an arm or a leg from prolonged exposure. For all of them, Grant’s pride had inflicted unnecessary misery.

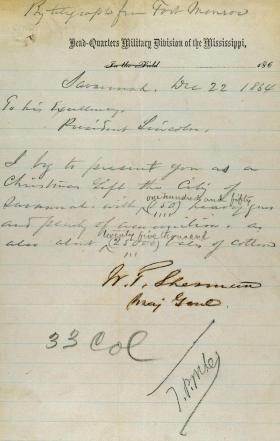

As I stated earlier, Cold Harbor also illustrated Grant at his best. He was not immobilized by the horrible loss. Instead, he planned and executed the next critical step. On the same day he acknowledged the defeat, he sent General Phil Sheridan with two cavalry divisions toward Charlottesville. Lee had no choice but to order cavalry General Wade Hampton to respond in kind, taking his cavalry to intercept Sheridan. The cavalry served as Lee’s eyes, scouting the enemy’s movements. Without Hampton near Cold Harbor, Lee could no longer keep an eye on Grant. Ten miles downriver from Cold Harbor, Grant’s engineers laid a half-mile pontoon bridge across the James River. Had Lee learned about the crossing in time, he could have destroyed Grant’s army. The Union army’s deliberate withdrawal across the James allowed Grant to “steal a march” on Lee. By Monday, June 13, the Yankees were safely across the James and Grant had set up headquarters at City Point (modern day Hopewell).

Please consider a longer read. New Garden is available on line from Amazon, Apple, and Barnes & Noble. Each website includes a “look-in” feature with the first few chapters of the novel. In Greensboro, NC, the novel is available at Scuppernong Books and the Greensboro Historical Museum Bookshop.

Trouble at Mono Pass, the sequel to New Garden, is available on line and at the referenced Greensboro locations. In California, it is available at the Mono Lake Tufa State Reserve (Lee Vining) gift shop, the Mono Lake Committee Bookstore (Lee Vining), and the Donner Memorial State Park Bookstore (Truckee, Californi