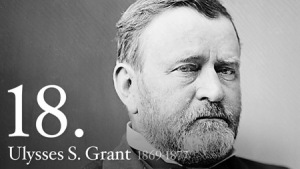

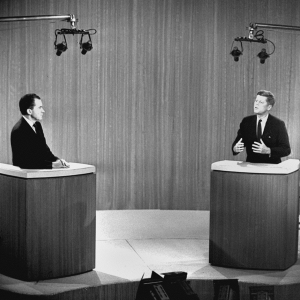

There’s nothing more historical than U.S. Presidential elections. With Ted Cruz’s recent stunning endorsement of Donald Trump, I thought a little political humor I wrote below might help us get through the current election cycle.

———————————————————————–

Brethren of the True Faith Mitch and Paul had spent over six years in the Desert, cast adrift among the sands. They took some solace from having prevented the Usurper from achieving most of his objectives. And now they smiled at one another, knowing the Usurper’s days were numbered. As they witnessed the fifteen from the Tribe and two outsiders enter the ring, surely, they thought, one of their peers will seize the mantle and lead the Tribe to victory in the Ultimate Battle against The Others.

“Surely, we can simply anoint Sir Jeb as our champion,” whispered Brother Mitch.

“No,” said Brother Paul. “There must at least be the appearance of a contest.”

“Perhaps, but why allow the Joker and the Witch Doctor into the contest? They are Outsiders, not Brethren of the True Faith.”

“Fear not, Brother Mitch. They won’t last among the seasoned warriors. We need their followers in the Ultimate Battle. Allow them to make fools of themselves. A misstep here and a misstep there, and they’re out of the contest.”

Fifteen Months Later

And, lo, it came to pass on the 462nd day, Brothers Mitch and Paul shielded their faces with their robes as the desert sands swirled around them.

“Why?” asked Brother Mitch.

“How?” asked Brother Paul.

“He made every mistake in the book,” said Brother Mitch. “He insulted all of the lords.”

“And even Ladies Carly and Megyn,” said Brother Paul.

“Low Energy Jeb, Little Marco, 1 for 38 Kasich.”

“And Lyin’ Ted,” piped in Brother Paul.

“Not to mention his impersonation of the crippled beggar who sits outside the city gates.”

“And that comment about blood coming from Lady Megyn’s whatever.”

“And everyone who disagrees with him is a LOOZAH.”

“Just how does he get away with it?” asked Brother Mitch.

“Too many contestants. The Joker charmed the Dispossessed. They didn’t fall in line this time.”

Suddenly, a great sand spout arose in the distance and headed directly toward the two great men. They ran in all different directions, but the sand spout shifted in turn and came to a halt before them. The sand spout disappeared as quickly as it arose, but in its place stood Lucifer in the guise of a well-tanned Wall Street banker.

“Who are you?” asked Brother Mitch. “Where did you come from?”

Lucifer smiled. “You have come to me many times in the past. Do not insult me by pretending otherwise. I heard you speaking poorly about The Fixer. I’ve come to ease your minds about your champion.”

“How so?” asked Brother Paul. “He is profane. He’s insulted half of the voters and all of the Tribe’s great leaders.”

“Tell me, Brother Mitch, what is your heart’s greatest desire?”

“To put one of our own on the throne. To have unfettered control of the Empire.”

“That is not the rumor whispered by all inside my palace walls.”

Brothers Mitch and Paul looked at one another. “Ah!” shouted Brother Paul. “Yes, we yearn to designate the successor to Brother Scalia on the Empire’s Court of Ultimate Justice.”

“And to what lengths will you go to fulfill your hearts’ desire?”

“Why,” said Brother Mitch, “we’d go to the ends of the Earth.” Brother Paul nodded in agreement.

“Then you would throw your support behind The Fixer?” asked Lucifer.

Brother Mitch grimaced like he was sucking on a lemon. Brother Paul ground his teeth like two stones in a mill. The two men gauged one another. Both nodded. “Why, yes,” said Brother Mitch, “if we knew for a certainty that would guarantee our choice of Brother Scalia’s successor, we would do anything.”

“Anything?” asked Lucifer.

“Anything,” said Brother Paul.

Lucifer pulled a tablet from his breast pocket and recorded their names. “If you bow down in humble submission to The Fixer, I shall fulfill your greatest desire.”

“But how?” asked Brother Mitch.

“How can you make such a promise?” asked Brother Paul.

“I am he,” said Lucifer with a smile that revealed bright sharp teeth and a forked tongue, “who fulfills the wishes of those who lust for power, just as both of you have done since your youth.”

“You are God?” asked Brother Paul.

Lucifer laughed. “Heaven forbid. I am he who was once favored by God. Nevermore. I curry favor among those who know the poor will always be among us, those who will sacrifice their very souls to achieve their worldly ambitions. You have always followed me and always will. Now, go, and just as The Fixer shall obtain his heart’s desire, so shall you.”

“And by what sign shall we know you can fulfill such a promise?” asked Brother Mitch.

Lucifer’s eyes opened wide to reveal tongues of fire, before simmering down. The Brethren’s faces turned white as a sheet. “Very well, I will provide you a sign. Before the sun sets four days hence, Brother Ted will prostrate himself before the Fixer. All the Brethren of the True Faith shall follow.”

With that, Lucifer’s eyes flared again as he spun into a sand spout and disappeared from their sight.

“What just happened?” asked Brother Mitch.

Brother Paul surveyed the landscape. “The Devil’s in the details, Mitch, but if Lyin’ Ted does the implausible, we just sold our souls.”

Short story copyrighted by J. Edward Gray/James Gray