This is the eighth in a series of articles in which I share my methodology for crafting a story, which I hope is both interesting and informative. Last week, I wrote about the California Gold Rush. This week, I turn to the Mission San Carlos Borromeo del Rio Carmel, better known as the Carmel Mission.

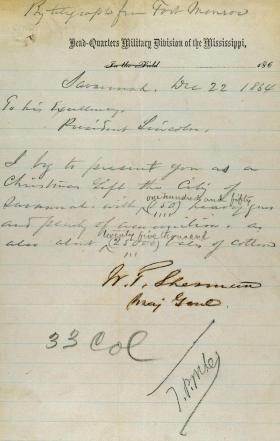

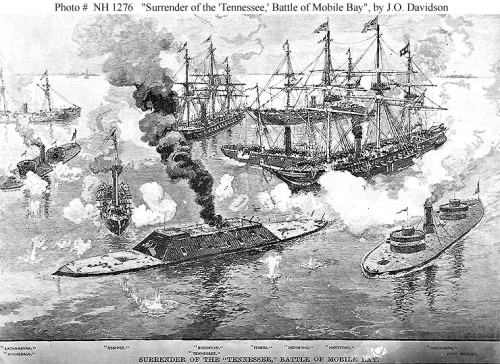

In the Writer’s Note for Trouble at Mono Pass, I inform the reader that the novel highly fictionalizes the mission, in that it was largely inactive from 1836 to 1884. Early in the story, however, the mission is dilapidated after years of having been abandoned. The mission comes into play as Union Army veteran Jack Grier returns to California after the Civil War. Jack hopes to build a relationship with the daughter he left with friends fifteen years earlier. Helen has been raised with the understanding that she is the child of Eli and Sofie Monroe. In this scene (pp. 27-29), Jack visits the grave of his wife Ileana, Helen’s mother.

Jack hitched Bishop to one of the posts outside the cemetery walls of the long-abandoned church. It was just as he recalled. Mid-morning, the fog had drifted into Carmel Bay. Jack took in the salt air and the warmth of the early morning sun as he walked into the small cemetery.

***

Meanwhile, Helen hitched Saladin next to Bishop, black like her horse, but a hand higher. She wondered who had come to this largely abandoned spot. She stealthily approached the entry and watched as the middle-aged man spoke to the grave that had attracted her curiosity over the years. She had made it her mission to learn the past of all those buried here, but had learned little about Ileana Cortes.

The mission’s dilapidated condition is described by William Brewer in the journal compiled while he served as a member of the Josiah Whitney survey, the first geological survey of the state of California. Up and Down California in 1860-1864: the Journal of William H. Brewer (New Haven, CT, Yale University Press, 1930). I relied on Brewer’s description of the mission in a scene where Jack’s brother Richard visits the Monroe family. Richard asks Sofie Monroe if the family attends services at the mission (p. 74):

“No. The mission is practically falling down. Squirrels have overrun the grounds and the birds have turned the sanctuary into an aviary. *** We hope to rebuild the mission someday. Helen is leading the campaign.”

From this point forward I exercise the fiction writer’s prerogative to take liberties with the facts. It is consistent with the fictional characters I have introduced into the history of the period following the Civil War. Helen successfully leads a campaign to bring the mission up to snuff. In the story I restore the mission to its current condition, absent the modern amenities of electricity and plumbing (p. 181):

Repairs had been made to the crumbling brick and stone exterior, which was resurfaced with fresh stucco. Terra cotta barrel tiles were laid on the arched roof. New bells had been installed in both towers. Miguel had repaired the eight statues on the altar wall, the two most prominent being Jesus on the cross and San Carlos, the Spanish saint for whom the church was named. Lois had carefully painted all of the statues with their original colors. Unlike American Protestants, whose marble statues were left unadorned, the Spanish had carved these statues from wood and painted them in vivid life-like colors.

Helen had ordered six two-tier wrought-iron chandeliers to light the center aisle of the church. Hector and Jorge Montoya had laid the red-tile floors. Other local craftsmen had built the black oak pews.

Thus, any visitor to the Carmel Mission will recognize the church as described in the novel. Had there been a Helen Monroe, I am convinced she would have brought the mission back to life well before it actually occurred.

Please consider a longer read. Trouble at Mono Pass is available on line from Amazon, Apple, and Barnes & Noble. Each website includes a “look-in” feature with the first few chapters of the novel. In Greensboro, NC, the novel is available at Scuppernong Books and the Greensboro Historical Museum Bookshop. In California, it is available at the Mono Lake Tufa State Reserve (Lee Vining) gift shop, the Mono Lake Committee Bookstore (Lee Vining), and the Donner Memorial State Park Bookstore (Truckee, California).

The prequel, New Garden, is available on line and at the referenced Greensboro locations.